Few weeks ago a tragic event happened in the very center of Warsaw. A middle aged, ordinary person, not known to really anyone outside of his family and friends set himself ablaze as a protest against the government policies. But, having spent a lot of time thinking about it and analyzing his letter left at the scene I came to the conclusion, that that letter and his action represent much more than just a political act. Just a political albeit tragic, protest. This might explain to some of my English-speaking friends my preoccupation recently with certain events. I was moved by it very powerfully and it had strong effect on my emotional and intellectual psyche. Still do. It speaks volumes on one’s ability or inability to deal with things in life that are so overwhelming that you feel totally defenseless, void of any hope for the future. We always accepted that deep personal emotion (love, friendship, betrayal, addiction, rejection, bullying) can push us to actions like that- but this was different. It arose from the feeling of state, political actions that were profoundly opposing to your own moral compass, your own sense of minimum justice, ethics, sense of goodness versus evil, right versus wrong. Not even economical at all. And so, tragic on an ancient, Greek scale of personal heroism, decision was taken. I call it ‘heroic’ for it did not involve any violence against the state, the government side. That would be an ideological terrorism.

His, chosen by himself, moniker (‘Szary Obywatel’ in Polish) should be translated not literally but in a sense that it represents in Polish: ‘Ordinary citizen’ . It sums up an overwhelming feeling of rejection of morally askewed reality. He was not a political activist by any stretch of imagination. The democratic opposition in Poland or large part of it, does not seem to understand the depth of such despair, either (the Government, of course, is not able to understand the profound power of such statement) – the grievances against the government are just the surface of the tragedy.

The true despair lies in the soul of his nation. The dark part of it, the egotistic, chauvinistic part of that soul. The, let say it loudly, ‘American’ type of ‘patriotism. ‘American first’ ideology was pervasive in Polish history for long time (of course, we called it ‘Poland first’ as we tend to believe that all things ‘Polish’ must be first). It is rooted in in our history of a state and nation edged between two very opposing civilizations: Western and Eastern , therefore a need to be a ‘guardian’ of sort of the dangers facing the Western (Occidental) set of values versus the Eastern (Oriental) set. But Polish values in that conflict were also mired in a very strong believe that it included (or is based on) a messianistic adherence to the Roman Catholicism dominancy. The great Reformation movement never really took a deep root in Poland. From ideas like that is a very short distance to feelings of being unique, special. Exactly the feeling of a mission of a lone Guardian.

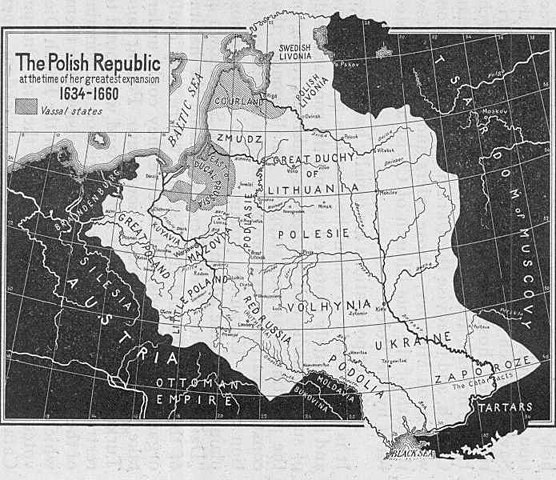

Yet, there was always (and growing over time) strong opposition to such a strange and confined values. An opposition that believes that the world evolves, that different set of cultures and values do not need to be in a constant battle, deathly struggle. That living in harmony is possible. And that humanism extends to all – not only to your own. Modern Poland is a ‘child’ of many traditions, multiple parents, so to speak. The most recent one was of course that of a Polish People Republic, a Soviet-dominated quasi sovereign state in very unfamiliar international borders. Poland, for the first time really in history, was confined more or less to ethnic borders. Hence was removed from all problems and blessings of co-existing with other cultures. Not on a serious scale anyway. It resembled very little the 1st Republic of Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth that for hundreds of years, since the Jagiellonian dynasty that begun in XV century, formed the essence of Polish state and it’s values. By the end of XVIII century Poland lost its independence for over a hundred years. To be re-born from the ashes of I World War in 1918. But what lead to the re-establishment of 2nd Polish Republic was of paramount importance. It was the deadly battle for the shape and soul of the nation and it’s state.

On one side was the grand idea of Jozef Pilsudski – the almost mythical hero of Polish independence, who imagined new Poland as a multi-national federacy of former parts of the old 1st Republic, the continuation of the old Jagiellonian idea. On the other side, the father of strictly ethnically Polish state, Roman Dmowski and his movement of Greater Poland (Wielka Polska).

These two ideas could not be further apart. Although, politically speaking, Pilsudski, at least for his lifetime, came out victorious (by large part because he was very skilled military strategist and did command the military forces and was highly respected on international scene) – his victory for restoring Jagiellonian state failed. For two main reasons: Ukrainians and Lithuanians did not want to be part of renewed Polish Commonwealth and the Dmowskis’s Polish nationalists, supported strongly by the Church hierarchy, did everything possible not to allow it to happened. Jagiellonian ideas and state would never allow them to achieve superiority and uncontested power. They would much rather give up thousands of square kilometers of old Polish state territory than allow for a multinational federacy. The fait accompli was achieved after great and total Polish victory in the Polish-Soviet War of 1920 (of which Pilsudski was the main architect) – the Peace Treaty was negotiated from Polish side by Stanislaw Grabski, very skilled politician. But a fervent believer in Dmowski, not Pilsudski ideas. To the astonishment of the defeated party, the Soviets – Polish delegation gave them huge swaths of land on Polish eastern frontiers.

Poland become by a large margins an ethnically Polish state. First time since medieval times, when nationality was really not an important concept at all. There were relatively big pockets of national minorities (today’s most western Ukraine , Belarus and Wilno district of Lithuania), a bit of spread German minority and relatively large Jewish population. But none of them could compete for political dominance or importance against huge majority of ethnic Poles. Hence the true long term victory belonged to the Grater Poland movement. Not total, but a measured one. The rest was done due the infamous Yalta and Potsdam agreements by end of 2nd World War that for all practical reasons confined Poland to strictly ethnic borders, with the exception of old Prussian state in northern Poland (presently Masuria region). That part was ethnically cleansed right at the end of the war by both German and Polish forces and consequently re-populated by ethnic Poles, often escaping the Soviet clutches in the lost Polish territory on the eastern side.

Yet the dreams of progressive, open to the world and not inward looking Poland did not die. Many Poles felt confined and suffocating in ‘one nation, one faith, one ruler’ concept. And wish to re-join the rest of Western Europe – the one we, as a ‘Guardian’, defended for so long in the old times. That posed a new hope. It got a huge boost when Poland was accepted as a full member of European Union. If we can’t have a Jagiellonian, multinational Poland than why not join a Union that is based one very similar pillars – a federacy of equals based on common goals and rules. It looked for a while that Pilsudski’s concept , decades after his death, was reborn in new form. But the nationalistic, paternalistic and bordering on fascist ideology (not Hitlerism – there is a long stretch between European fascism and it’s extreme end, Nazism) of Greater Poland did not give up. Due to many mistakes and lack of steadfastness of former center-right liberal government the last election was won by populist Law and Justice Party. That party, although not ideologically part of some grand coalition of Greater Poland – attached itself to many slogans of the nationalistic movement of Roman Dmowski. And the fruits of permanently loosing Polish Jagiellonian legacy in that infamous Polish-Soviet Peace Treaty of 1921, become very visible. Open, multicultural, progressive Europe scared many Poles. It wasn’t romantic Paris of XIX and early XX century, it wasn’t Italy attached as an obedient child to Vatican. It was a Union of mostly nation-states but very much open to multiculturalism, to immigration, equal rights for minorities of all sorts: ethnic, religious, sexual, gender-based. More or less it was a Union of modern, XXI century democracy. They had time to build it and get used to it in the past 70 years since the end of the 2nd World War. Poland did not. And it scared many of them. Many Poles felt better in their mythical role as a Guardian of Europe, of the West. When you are a guard of the fortress, you cannot allow yourself the delicacies of an ordinary citizen – you are a soldier who must be disciplined. It was just sad that … Europe no longer needed such a devout guard. Europe was doing rather fine without a fortress of tall walls. But we, Poles, knew better than Europe what Europe needed! Africa is for Africans, Asia for Asians and Europe for Europeans. White and Catholic. Never you mind the Lutherans and other Protestants or silly Anglicans. Of course, one day they will come back to the Mother Church. It has been only 500 years – that’s nothing in the face of eternity! LOL.

It might sound silly at the end of previous paragraph. But it is not. It is very crude and simplistic generalization of today’s Polish society – but a true one, nonetheless. It is very tribal at its core, still enslaved by the chains of it’s painful history, still unsure of it’s own inner strength. And – in a country where history plays such an important role in everyday life – very ahistorical.

Not to continue and changing it into a long essay: the “Ordinary Citizen’, who set himself ablaze in Warsaw could not live any longer in a country that rejects these lofty, humanistic ideas of coexistence. He was tired of being forced to be a guardian. And therefore his conflict, the essence of it, was not solely with the current, chauvinistic populist government. Governments come and go. It was with his countrymen. With his nation. I am neither sure nor know if he spent much time thinking of differences between concepts of Pilsudski or Dmowski for Poland. But I am certain that these two conflicting concepts lay at the very base of Polish society problems today. The difference of remaining oneself while fully respecting the ‘otherness’ of different opinions and rights and being just a soldier, a guard, who simply follows orders. And that’s why it was so profound. So heroic on an ancient Greek scale. And so terribly sad, chilling to the core.