Bogumil Pacak-Gamalski

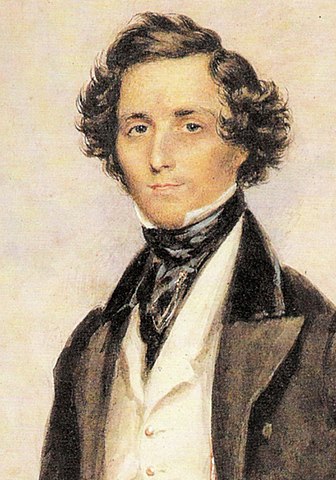

Few words of personal explanation. Of my wonderful life with my beautiful husband, lover and partner, John. Life that tragically ended with John passing a year ago. Yet life worth every moment, every second. Music, music – it has been such an important part of our life. Through music – in all forms, shapes, and styles – we understood each other deeper, fully. Like the name given by German composer Felix Mendelssohn (1809-1847) to his ‘Songs without words’. Love truly does not need words. As in any true process of creation, words – if used – are only a mere ornament, part of the mechanical structure. True creation begins and ends in a sphere of senses: sound, smell, touch, feeling. Everything else is just a noise.

Therefore, when I walked that wintery evening from Henry Street to Coburg Street and to St. Andrew Church for my normal rendezvous avec la musique – he walked there with me.

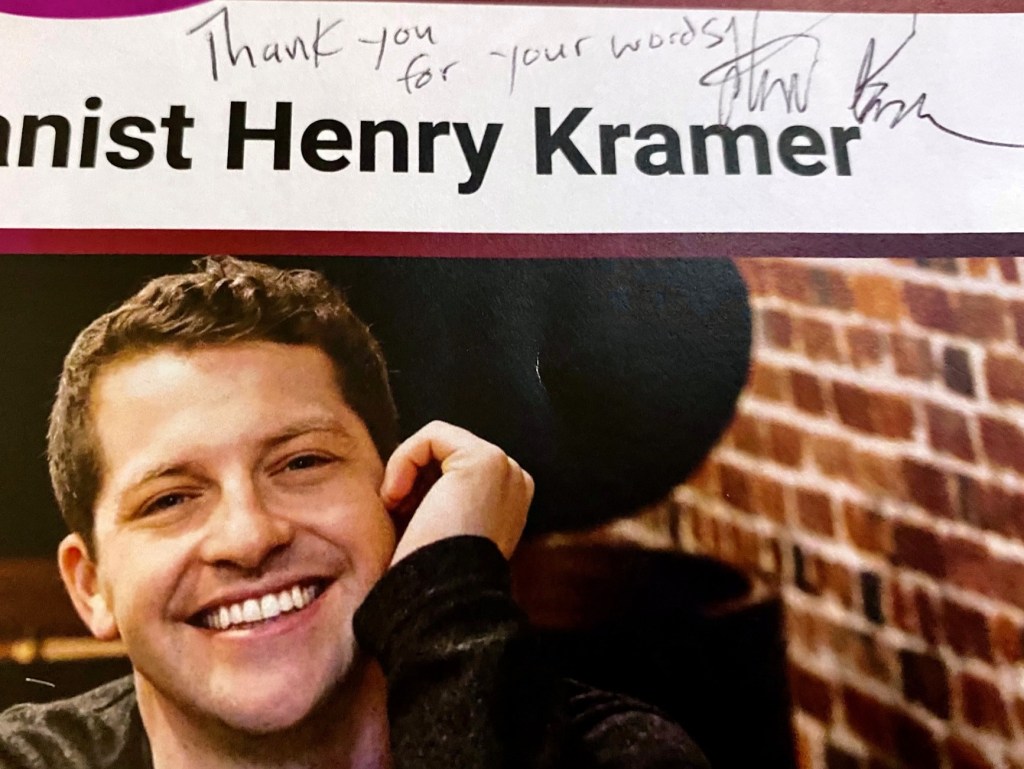

What a wonderful rendezvous it was! It was an immense pleasure to listen to the music played by the most gifted pianist, Henry Kramer. Kramer is an American musician recently being offered a teaching position in the Faculty of Music at Université de Montréal, and because of the proximity, he was able to come to Halifax and give us a taste of talent. What a treat, indeed.

One award (among many others) I have to mention is the American National Chopin Piano Competition in Miami, where he claimed the 6th spot in 2010 (the First Place automatically awards the winner a spot in the top piano competitions of the world – the Warsaw International Chopin Competition). But there was a connection to that famous Warsaw Competition: among his jurors was the former 3rd place winner of the said International Warsaw Competition, Piotr Paleczny. I was lucky enough to hear Paleczny playing many years ago during that Competition in Warsaw and to know him personally. He was, as a young fellow at that time, a very sweet guy. And truly fantastic piano player.

Henry Kramer missed that Warsaw Competition ticket – but he did not miss the 2016 prestigious and top-ranking Queen Elisabeth Competition in Brussels. And he got the Second Prize – that is a ticket to just about all concert halls in the piano world.

I was not in Miami to hear him personally there, but remember his concert in Seattle. Remember him well enough to make a note of his playing: don’t forget his name because you will hear of him.

Back to Halifax. Have a chance years later to do that. To be at his concert. How can I describe the overall feeling, reaction? I will use a term I don’t remember using before in any of my musical reviews:

Henry Kramer is a pianist of a very elegant way of playing. That it is. Elegant way of playing. You could say: bravado, astonishing, lively, emotional, technically brilliant. But after listening to him intently, paying attention to how he treats not only the music but the entire piece that makes a player, his arms and body and keyboard, pedals, and the entire massive instrument a one-piece, one symbolic union – that is the term that came to me: grace and elegance.

And what a good term, when you play music submerged in a very specific time of European chamber music of early romantics. Time of Shuberts, Mendelssonhs, and to a lesser degree even Liszts (Liszt belongs more to the next epoch – Romanticism). A time when musicians produce an extraordinary amount of compositions (almost in manufacture-like tempo) to appear in a multitude of salons of political, and Church dignitaries, aristocrats and extra-rich townsfolks. Time of Early Romantics. These were not huge concerthalls, or musical theatres (there were some in big cities – but that was a rarity, not a rule). The salon for chamber music was small, and the guests were not as plentiful. If you play the same music more than a few times – the opinion arises that you are done, finished. You emptied yourself and can’t compose anything anymore. So they did compose. A lot. Franz Schubert composed 20 sonatas (not all of them in a finished form) and a number of larger pieces: 12 (13?) symphonies; circa 10 Masses; over …. 1000 (that is one thousand, no mistake) songs with at least one instrument and many more occasional pieces in different form. No, he was not eighty years old, when died. He was … thirty-one. Show me a contemporary composer, who composed half of that volume, I dare you.

Was he a great composer? No, by any means. But he was an important composer and very talented. Had he lived decades longer, had he achieved financial independence and powerful support from powerful patrons – chances are he would have had time and space to compose a few timeless and extraordinaire pieces of music. It was also a time when music was composed in a very strict and form-fitting format. Just as poetry in classic times. The next generation started slowly to dismantle that construct. And then came Gustav Mahler, followed by Schoenberg with his Second Viennese School and music was never the same again, LOL.

The old Saint Andrew Church in Halifax was a perfect setting for Schubert’s music and for the elegant style of Henry Kramer. The main nave offers wonderful acoustic and being of Anglican (in Canadian, United Church form) type is not too ornate and void of the weight and ballast of Catholic big churches.

From the moment Kramer appeared on the stage with a short introduction to the music – he won the audience with his pleasant way of greeting and talking. There was no ‘pomp and circumstance’ – just a warm and subdued tone.

From the first keystrokes, he was very attentive to musical detail, to the phrasing. Schubert’s Piano Sonata in A Major seemed to be written for him. The Allegro Moderato at the beginning was lovely. It’s a relatively robust tempo but the two melodies and two distinctive themes lead to a lovely passage. And his brilliant way of slowing ‘things down’ in Andante is just that: have time to ponder, exclaim, and reflect. At a certain moment, a listener not familiar with this work might think – that it is, finite. Perhaps little annoyed that it happened so soon, LOL. Kramer used the intervals splendidly, they were very pronounced as the composer intended.

But forget the intervals, forget the delicacies, the sublime. Here comes the Allegro. Better check your seatbelts! This is a pianist (a good pianist) paradise: time to awe and conquer the audience. And he did. The bravura almost and brilliant style shine here with dances, and passages. The keyboard is used in its entire length and the pianist must grow two or three more fingers, LOL. But it is truly a pleasure to listen to it. Even if you are not an enthusiast of early Romantics (just like me) – I still can come and listen to the entire sonata again – just to enjoy the finale! Bravissimo for the artist!

After Schubert music, Kramer opens to us the world of two siblings, contemporaries of Schubert: Fanny Mendelssohn – Hensel (1805-1847) and Felix Mendelssohn Bartholdy (1809 – 1847). Both siblings were very close to each other.

Felix was well well-known and very much accomplished composer in Berlin’s circle. His sister never (partly because of her father’s opposing views) accomplished such a fame during her lifetime but her compositions show a good measure of talent and ability. She was also very respected as a musician by her devoted brother, who often asked for her opinion and advice in his own works. As it happens from all their works the most famous ones often played even now are their songs. Or rather ‘songs without words’ (Lieder ohne Worte), as was the name Felix gave to his most famous composition. There is a story that at one-time friend of Felix offered him to write words for his ‘songs’. The composer is said to respond: “What the music I love expresses to me, is not thought too indefinite to put into words, but on the contrary, too definite.” What a lovely and indeed precise response!

The pianist played Fanny’s 4 Lieder for Piano, Op. 8 (no.2 Andante con espressione and No.3 Larghetto), and Felix’s Songs Without Words Op. 19 in E Major and Op. 67 in F-sharp minor. It was a pure musical pleasure. His elegant way of playing was at its best. The depth of emotions coming from the sound he was producing was truly touching. I remembered years ago when I listened to the incomparable Jan Lisiecki playing the extremely difficult and technically challenging piece of Ravel’s Gaspard de la nuit and I thought: how this very sweet and happy young man (I have known Jan Lisiecki since he was fifteen years old very sweet boy when I did my first interview with him) can evoke the atmosphere of pure horror and terror so plainly, so vividly? Talked after his play with him about my question. And his answer was as plain as it could be: it is not enough just to play – you have to feel it inside you, you have to take that symbolic journey to that place, that moment and then transfer it to the tips of your fingers. Just playing every note, in exact tempo is not always enough. And I understood that instance what he meant. Of course. It is so plain. The feeling, the emotion. Listen to famous, dramatic singers of opera! The words are almost comical often. If you just sing them – you could almost laugh, like a satire, not a tragedy. It is the emotion, the timbre of the note you play, and the spirit of the sound you produce that signifies emotions. This is exactly what Kramer achieved when he played the Songs Without Words. And I repeat: with that musical elegance.

But even the best of us must give up sometimes the comforts of elegance. When you deal with Franz Liszt’s Piano Sonata in B minor, S. 178 you really have no choice. When the Paganini of grand piano composes music that should rival Paganini’s Caprices – elegance and etiquette go away. I often compare him to Tina Turner and her singing career. Was it elegant? Heaven’s forbid, no! Was it great? Of course, it was a wonderful madness! Would Henry Kramer, that elegant musician be able to play such music, to forgo his comfort zone?

Oh, yes. He did it to my delight. That was not a summery evening stroll through the meadow. It was a full gallop! Not even of one horse – it was a herd of wild horses. What a choice for the finale and what a stamina to do it after already playing so many pieces.

Liszt’s sonata is one of his late compositions when he composed mostly for pleasure and not to gain popularity or earn money. It is in a way also a break with the established way musical forms were composed. Sonata, as a sonnet in poetry, has very strict rules. Three, sometimes four pieces. You state your musical subject in the first part, elaborate more freely on it in the middle, and finish with a recapitulation of the first statement. But Liszt decided to do away with two distinct pieces and used just one. Try writing sonnets in the form of elegies. In a way, he liberated composers from the strict and tight corset of existing musical architecture. Today everyone understands it. We have gone through modernity and postmodernity. But at that time … it received scorn from all the greatest composers. Clara Schuman (Liszt dedicated it to Robert Schuman) said it was ‘merely a blind noise’; Johannes Brahms apparently fell asleep while Liszt performed it; similar scorn was shown by Anton Rubinstein. The only exception was Richard Wagner. Yet, by the early XX century that ‘blind noise’ was recognized as the pinnacle of Liszt compositions. Times are changing.

I can’t tell how many times I heard that amazing, powerful compositions being played by many wonderful pianists. In a way, my favorite was the recording of it by Kristian Zimerman, one of the outstanding pianists of my generation in the entire world.

But the way Kramer played it was more than satisfied. I listened with full abandonment and total ecstasy of my sensory powers. No surprise that after that accomplishment the audience would not let him leave the stage. The standing ovation had no end. And fully earned. To no surprise, he had no choice but to thank the audience with two extra encores.

We finished with a nice chat and my congratulations for very well-presented program and excellent play. But I started the conversation by thanking him for transferring me that evening from Saint Andrew Church in Halifax to Carnegie Hall or to Vienna Philharmonics.