Bogumil Pacak-Gamalski

What do you think of poets? Ephemeral creatures? A poet must be someone, who lacks persistence and discipline to write a solid novel? Let’s say five hundred pages long? Yes, you have seen, perhaps have one on your shelf big book by some poet you like. It is hundreds of pages long. Good. But such a book most often is an editor’s work of compiling, in some sort of order, hundreds of separate poems written throughout a lifetime. Generally speaking, a poet publishes a book (in modern times) that would be 20, 30, or maybe 50 pages long.

The times of huge volumes of Goethe, Mickiewicz, Byron, Pushkin or Chaucer are gone. Their work is generally called by a broad definition a ‘long poem’. They are still being composed by some – but hardly to the extent of times gone. Imagine one of the oldest known long poem by Abul-Qâsem Ferdowsi Tusi, a Persian poet in the X century, who wrote “ Shahnameh” – a poem of 50,000 couplets (two-lined rhymed meter). It is the longest ever written by a single poet in recorded history.

It is not only a strong talent but also a sign of unusual perseverance. Not very common in the XX and XXI centuries.

But – what is difficult for a mere man-poet doesn’t have to be too difficult a task for a woman-poet (women are generally much better in keeping their focus on goal than menfolk, LOL).

On a recent visit to a favored literary café in Halifax, I came across a huge volume of such long poem. The medium is mixed: regular-versed poetry and poetic prose verse. But all in the context of the same subject and telling the same epic (if ‘epic’ is the right term for such a subject) story. It is merely a booklet of … 1009 pages (one thousand nine). And the poetess devotes her talent to tell the story of … man.

I am talking of Anne Waldman. Waldman was (with Allen Ginsberg) a pivotal author and activist of the Beatniks movement in culture and counterculture of the 60. and 70s. In a way – a child of the Greenwich Village community of New York at a time of pivotal struggle with the Establishment. How many times have I longed to be there at that time! But a generational difference made it impossible.

Poets and artists who devote their talent to a cause that is larger than life give me wings to fly. I feel sorry for poets of ‘ivory towers’ or Parnassus’ peak. Their own glory and fear of missing the bus to immortality make me laugh.

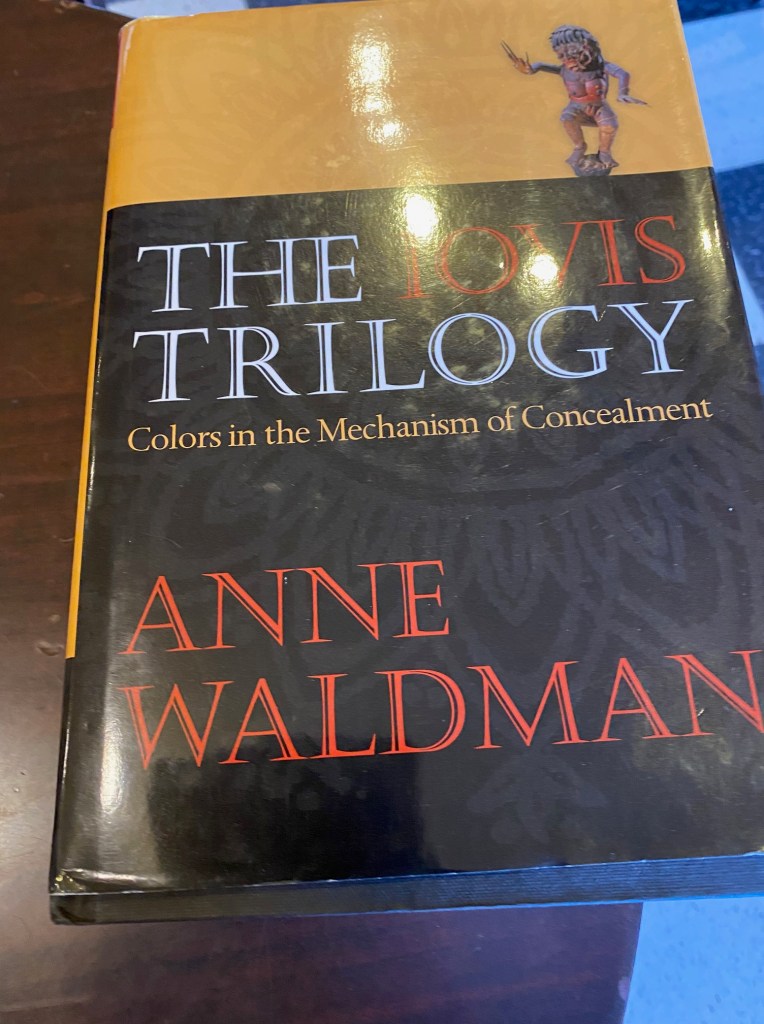

Back to Waldman long poem, though. To “The Iovis Trilogy. Colours in Mechanism of Concealment”[i]. She spent twenty-five years writing it. That is perseverance, I must say.

Iovis is of course the epitome of Man. He is, formally speaking, an early Roman central god, an equivalent to Greek Zeus. The one, who looks after the order of humans. And the world of humans is the world of man. Period. Even lesser goddesses do not change that paradigm, that foundation.

Waldman does not detest men, a man is not her mortal enemy. She tries to show him that she sees his ways of trapping her-woman, of claiming her as his. A thing on the mantel. Necessary, needed. But never fully equal. Iovis is so set in his ways, that he might not even realize it anymore, he might not see the ways, the channels, roads that he built over thousands of years. They just are, aren’t they? A natural order of things: as trees, streams, mountains, and plains.

Right at the very beginning, she addresses him directly:

Dear Iovis:

Thinking about you: other in you & the way

You are sprawling male world today

You are also the crisp light another day

You are the plan, which will become clearer with a

strong border as you are the guest, the student

You are the target

You are the border you are sometimes the map

You are in the car of love

You are never the enemy dull & flat, dissolving in the sea

Illusion lay it snare, you resort to bait, to tackle me

Our day is gone[ii]

Waldman states her case right at the beginning: I have a clear picture of you and your tribe – meaning the whole tribe of men – ‘you are in the car of love’. He lays bait and snare to make her-women his. To make her love him. It doesn’t change a bit any of these ancient roles, a fact that he too loves her truly. But it is her, that will become his – not the other way around. And she says flatly: our day is gone.

She admits the history of them, the ancient times going back to Sanscrit writings and dwellings:

As I say this to you, the furniture is rearranged in a sacred text

The room is now long, the room is tall, the room is male[iii]

It isn’t only the imagery of the past going to the beginnings of recorded history – the poet brings a throng of marching dead lovers, the ones that show themselves on ‘All Hallows Eve’.

It is a monumental poetic work. And, at the same time – it is very contemporary poetry. This comes as a surprise since the author submerges the reader in a tremendous history of humankind and human relations. Especially the love-friendship relations of men and women. She goes back to the origins of patriarchate, and uses Buddhist teachings to explain it, to uncover the lost or true meaning of that history. But it is a result of her actual time. Her time in that particular moment in Greenwich Village in New York and all that was going on at that time. Therefore the poem is also a political call ‘to arms’. To rearrange the furniture, if you will, of contemporary discourse and intersex relations. The man is not portrayed all the time as ‘an enemy’, ‘enslaver’. He too is being enslaved by his own actions. By the world of misogyny. Her long poem is sometimes compared to Ezra Pound or even to Dante’s immortal ‘Divine Comedy’ and William Blake prophetic books. I certainly would never go as far. Dante’s work is by any account a work of true genius and incomparable to her work. But, on the other hand, I have found her poem much better written and arranged than Blake’s strange and difficult-to-follow volumes. It is not an example of a literary ‘testament of time’. Indeed, it is very contemporary. Interesting to read – but I doubt very seriously that it will be red 50 years later or centuries later (as is still the case of “Divine Comedy”).

In the middle of her work, Waldman admits certain resignation, the impossibility of escaping raw emotions, raw needs, and desires:

and the point along heart meridian

dissolves further down

legs already given out

je suis fatigue

Auto da Fé[iv]

Conflict, fighting for change is tiring, perhaps exhausting (je sui fatigue). The moment she does it – she performs a spiritual act of auto da fe, as Voltaire’s Candid. And an act of faith paid by violent death in the flames. Iovis explains that such an act is a:

trance- fire

Came trough

trance Atlantic

to breath the l’air prehistorique[v]

It is important to notice the play of the words ‘trance Atlantic’ versus ‘trans Atlantic’. I will state again that in her poem, in the interconnectivity of her-woman with Iovis – everything is in a trance. Should I try to remind you of the contemporary context again? Who was not in some sort of trance in Greenwich Village by the end of the sixties? Certainly not many people among the artistic crowd.

I must say that I found the entire long poem amusing and interesting to read. Both by her poetic skill but mainly as a testament to the time of cultural counterrevolution in America. But my interest vanned somewhat halfway through the book. By page 350 I couldn’t go anymore. Went straight to the last chapter (which was very personal and interesting). If you have the time – I would happily suggest reaching for that volume. It is a good temporary poetry and an excellent example of that particular time in American literature.

And I do hope that Iovis has learned a good lesson and is a better man now. As a partner of her-woman. Not his-woman.

[i] Coffee House Press, 2011. Minneapolis; ISBN 9781566892551

[ii] ibid; p.17

[iii] ibid

[iv] ibid; p.257

[v] ibid; p.258