Bogumił Pacak-Gamalski

What an interesting concert it was. Not often do I go listening to very young (I mean – kids, not even late teens) pupils of a musical school. Sometime maybe to very young prodigy – such was the case of Jan Lisiecki[i] (Jas – as I still call him, despite his international stardom), but not to entire group of really young kids. Remember going to recitals in an old Warsaw Conservatory of Music on Oczko Street or Vancouver Conservatory of Music – but they were young students in their late teens or early twenties, not kids by any means.

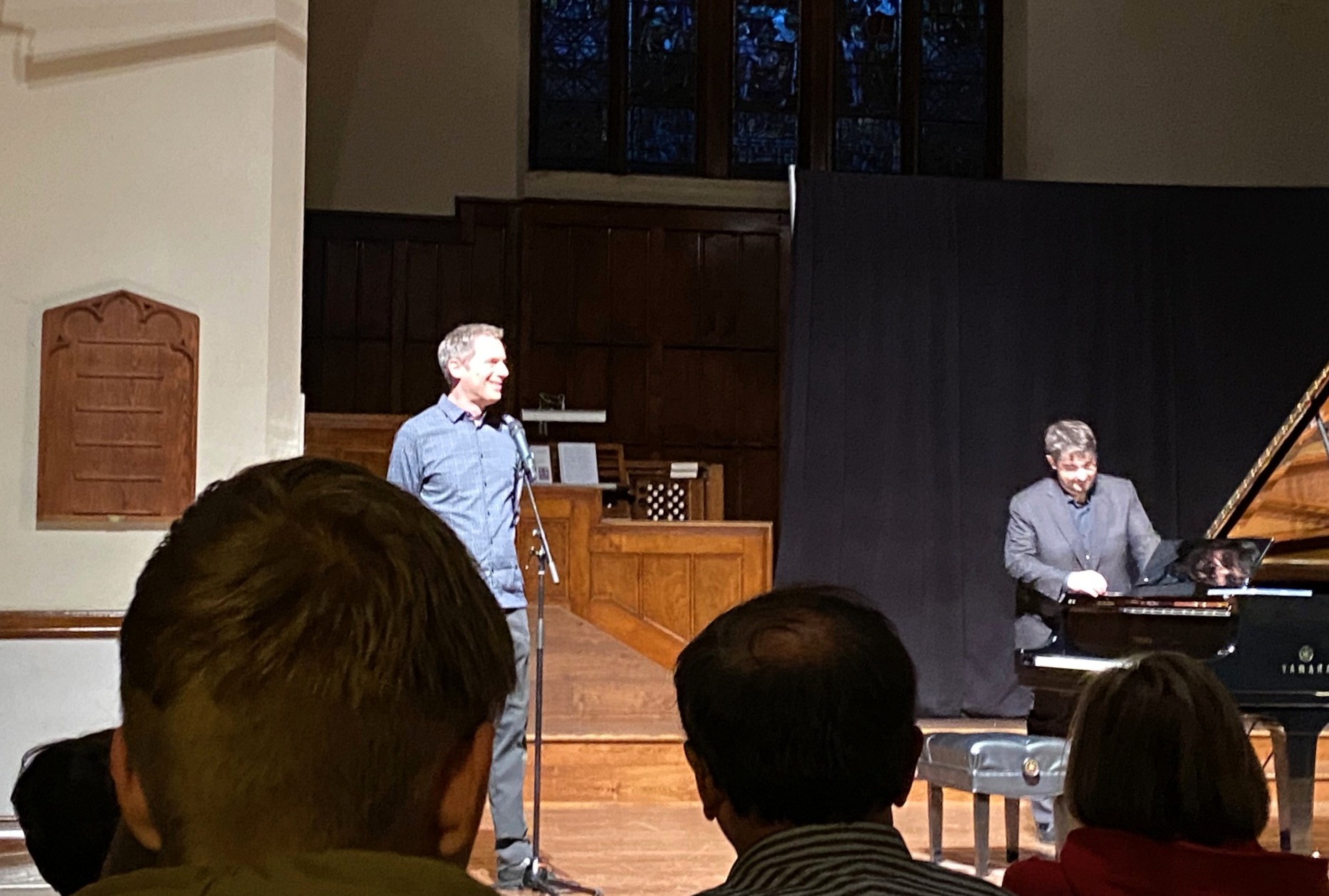

Truth being told, I was looking mostly to the second part with Zbigniew Raubo, whom I didn’t listen to for a long time. I mean in person, on stage, not from electronic recording.

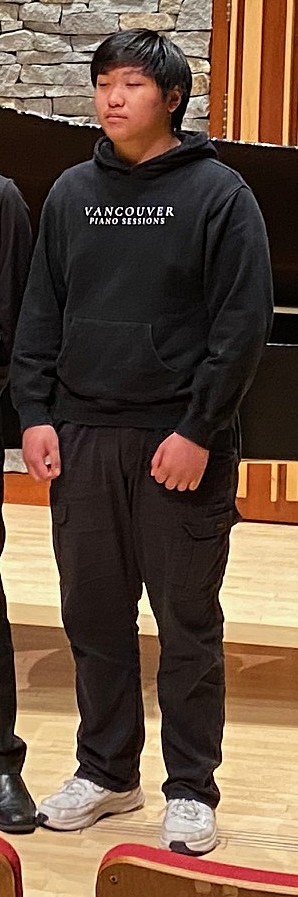

But it was a very nice and happy surprise. They all sort of knew what they were doing by the keyboard, LOL. I’m sure they had to overcome a huge anxiety being in front of relatively big audience full of their teachers, parents, and some famous piano players. Part of their studies is certainly guidance for avoiding stage fright, but still – stage fright is a powerful foe.

The School concert hall (on the back of the proper VSO “Orpheum” building) is very nicely designed. It is more long then wide and instead of acoustic paneling it plays on the original shape of the room. To assist the travelling of the sound and avoid echo (horror!) large wooden beams on the old masonry walls were attached aiding not only the harmony of sound, but also a pleasant visual effect. I would think of modest seating capacity circa 150 seats, maybe with added rows of chairs up to 200.

Of course it would be wrong to write a typical review and trying to be smart by pointing to minor mistakes, imperfections of the young students playing, especially if all of them were well prepared. Therefore these are just going to be general notes of what they played and overall impression how they did it. After all, music is just another way of writing a story. It just uses different alphabet, instead of letters it writes in notes; instead of grammar rules and signs, it uses its own grammar: crescenda, flats (skewed letter of ‘b’ ha ha), sharps (#), and on top of that there is different annotating for major and minor scale. Not to mention that composers sometime make their own personal written advice how a piece should be played. But enough of that, It is not a beginners course of music.

Sophie Meng was very first to perform, a diminutive frame of very young girl, perhaps the youngest of them all. The huge Steinway piano looked like a black mountain in front of her light figure – impenetrable and towering. I observed her hands as their traversed the keyboard and was wondering how much she has to stretched them to cover an octave! That observation leads to another: small-frame pianists play with their hands on the keyboard, full-sized (what a terrible description, LOL) use their fingers, which must be less exhausting and tiring. In more grueling concerts you will sometime find pianist submerging their swollen hands in icy water to remedy their muscle and joint stress.

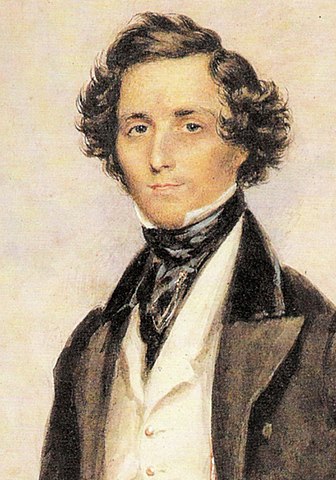

She played very pleasant a Mazurka in C Major, Op.24. I let myself follow her play into the dream: like she was not playing – she was running on some green field with young Frycek (diminutive of Frederic). That was a nice vision a young Chopin would certainly approve of. What was particularly worth noticing, was the way she kept a perfect harmony by keeping the main musical theme of the composition always in the background, always present. Even if not played at that moment – it still lingered in your memory.

Charlotte Deng played Scherzo in B-flat minor, Op. 31. Herself looking like a cherub, she easily displayed a maturity that surprised me, perhaps a dose of self confidence? These could be uplifting or dangerous emotions for a very young player.

Her physical control of the instrument was visible, as was her aura of confidence. At times maybe the music came a tiny bit too strong, too forte? I smiled – an ‘old hand’ in a body of a youngster. Her posture at the piano, the way she used physically her arms and hands on th keyboard again emanated maturity. Just that the ‘maturity/ was perhaps more a stage performance, not an inner feeling since at moments the music was overplayed on forte. Naturally the true poetic soul[ii] of the music returned fully with the arpeggios. The finale naturally goes back to first section, and was played very well with an elegant coda.

Stephanie Yueyou Liu presented the audience with Waltz in A-flat Major, Op. 34. Her keyboard skills were excellent. At times I thought I am loosing the smoothness of the waltz melody though, as the keyboard skill muted a bit the soul, yet – she re-paid in a very wonderful finale.

Brain Sun played Ballade in G minor, Op. 23. I felt that he thought very deeply of the structure and meaning of the music he was going to play. Would like to listen to his interpretation once more, as for some reasons his intervals and use of pedals seemed a bit odd – and the full impression escaped me. Fackt that I nonetheless wanted to hear him again simply meant that I liked it, That’s easy – and at the very end that is all that matters.

Joshua Kwan played Barcarolle in F-sharp Major, Op.60. His play quickly established very strict control of the instrument, of timing. No rushing, no ‘elongation’ of notes. Smiling to myself, I thought that this guy does not need a metronome on the piano.

Brian Lee in Etude A minor, Op.25. He would let his right hand in quick passages to overtake, or silenced his left hand leading the subject and tempo. It is a difficult composition for a young player. It provokes almost to fly too high, to shine in it’s sounds. Perhaps in its bravado-like finale it is hard to stress the last notes, as you mind is still overflowing with melodies of previous section. He played with full bravado. I must say that one must admire the guts of very young player (or teacher, who tells him to play it, LOL) choosing it. It is just about the most difficult technically etude Chopin composed. Frederic contemporaries in Paris didn’t like it that much exactly for that reason – for being technically challenging to play.

Thus ended the student’s part. After the intermission we were served full musical dinner with three very different and very popular dishes. Maestro Zbigniew Raubo, s’il vous plait.

Zbigniew Raubo, although dedicated very much to his teaching of music, is an accomplished concert pianist himself, known to many of the best stages of the world both as a pianist and with an orchestras. He finished Katowice’s[iii] Karol Szymanowski’s Academy of Music, where he later become a pedagogue himself. During his career he took part and received top prizes and distinctions in many European music festivals.

Currently he teaches at the Vancouver Chopin Society associated with VSO School of Music. His partner in the teaching staff there is another great acclaimed Polish pianist Wojciech Świtała and last but not least by any means – young Polish-Swedish[iv] pianist, Carl Petersson.

I will not write a typical review of maestro Raubo concert in 2nd part of that evening. Would be unfair to the young participants – his and his colleagues’ pupils – to even try to draw any comparisons. That was an evening for the young ones. The ‘master class’ of Zbigniew Raubo was a glass of champagne to the audience for showing up to celebrate his students achievements. Just a list of Chopin’s compositions he presented: Polonaise C-sharp minor, Op.26; Mazurka A-flat Major, Op. 50; Mazurka C-sharp minor, Op. 50; Nocturne D-flat Major, Op. 27; Waltz A-flat Major, Op. 34, and Polonaise A-flat Major, Op. 53.

Yet, one distinction I must make. Chopin’s music and perhaps hundreds of concerts of his music I have listened to is in a way almost like some familiar songs you sing sometimes to yourself without even noticing it. It become sort of part of your nature, grows on you. Especially if it was a normal part of your very early childhood, when you don’t treat it with reverence, but as something normal, part of the routine. The reverence and deeper understanding of it comes later, as you grow up. It makes it a bit like a emotional but also intellectual luggage, not always very convenient. There are (very rare indeed, thank god) concerts you wish you didn’t buy the tickets for. There are (even more rare, phew!) concerts you just wait for the intermission to … leave and go home such is the disappointment. Because you know so many of the compositions, you heard them so many times. But I still find (not as often as many years ago) musician, who just takes my breath away. It has nothing to do with brilliant playing born out of amazing skills. On some level you expect it, too. No, it is the other part, one beyond the skill of playing. It is capturing the essence of the poetry of particular composition, the emotional part of it. The soul (yes, maybe not all humans have souls – but true art always does, without exemption).

Zbigniew Raubo did it to me with his interpretation of Chopin’s Nocturn in D-flat Major. I can’t remember when, was the last time I was touched by that composition so strongly. Music, like a poem, has a story to tell. At times it is not even the story the composer intended or thought of. No, it is your story, story getting life form as you listen to that music. I heard it that evening, intertwined between notes, phrases, and letters and words. Can’t remember the exact text of the story – but remember hearing very clearly, as the music was played. Thank you, Zbigniew Raubo.

from top left:

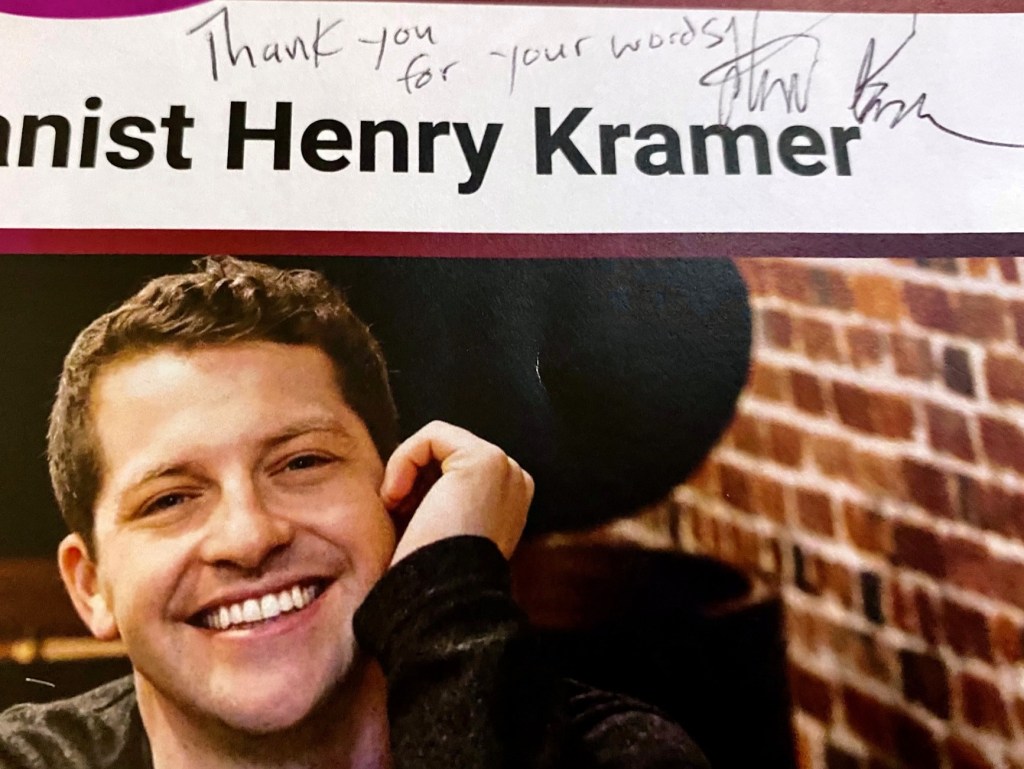

pic. 04 -Patrick May one of the top organizer of Van. Chopin Society; pic. 06 – prof. Wojciech Świtała, famous Polish pianist; last picture – Board of Directors of Van. Chopin Society and from left: W. Świtała, Zbigniew Raubo and last Polish-Swedish pianist Carl Petersson.

[i] Jan Lisiecki – Classical Pianist

[ii] Robert Schumann compared it to ‘Byronic poem’

[iii] the capital of Silesia region in Poland

[iv] born In Lund, Sweden – his parents are Swedish (father) and Polish (mother). Graduated from Danish Royal Academy of Music.